June 30, 2020

Tracing: Get It Done, Make It Permanent.

Key Takeaways

- The U.S. needs a comprehensive tracing program to safely reopen an economy hobbled by COVID-19.

- State and local governments must hire between 100,000 and 300,000 workers for a comprehensive, nationwide program.

- These workers will need training on tracing work, and on how to be culturally sensitive to the needs of communities hardest hit by the pandemic.

- The tracer job description parallels that of community health outreach workers already working in communities for some payer and provider organizations.

- Permanent funding for tracing positions would empower state and local public health departments to address healthcare access inequities and the social determinants of health.

- The same workforce could deploy expeditiously when future pandemics hit.

The U.S. has unleashed a dangerous science experiment on its own people. Tens of millions of Americans are resuming routine economic and social activities before public health authorities implement a comprehensive COVID-19 tracing regime.

The early results are in. During the first two weeks of June, new cases spiked in states that have not imposed broad stay-at-home orders or have moved too quickly to reopen their economies. Florida, Texas, Arizona, Alabama and North and South Carolina are seeing some of the largest increases in new cases. [1]

The federal government has abdicated its responsibility. President Trump’s failure to enact a nationwide testing and tracing program, coupled with him encouraging early reopening in states ill-prepared to pounce on outbreaks, is reeking further damage on an already reeling U.S. economy. For want of a $10 billion testing and tracing program, employers, stockholders and employees have been hammered by losses that now measure in the trillions.

The states that are having the most success tamping down the pandemic are those that are ramping up their tracing programs. They include Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Illinois and Washington. However, even in these states, case rates differ. Large urban areas with large outbreaks are seeing declines in new cases, while some rural areas and small towns are seeing upticks.

A successful tracing program requires a small army of well-trained workers. By some estimates, the nation needs to hire 300,000 tracers nationwide, only 37,110 of which were on the job as of mid-June 2020, according to an NPR survey. [2]

TRACING IS POPULATION HEALTH

Tracing is hard. It involves one-on-one interviews with every person diagnosed with the disease. Someone must ask patients stricken with COVID-19 to identify everyone they’ve come in contact over the previous few days. Then someone must contact those people, encourage them to get tested and even quarantined for up to two weeks.

Tracers need the cultural sensitivity to deal with the diverse communities that have been hit hardest by the disease: African Americans, Hispanics and immigrant enclaves. They need the communication and persuasion skills to deal with employers who operate unsafe work environments. They need support from agencies that can provide food, housing and other social services for people who need help while quarantined.

As difficult as all that sounds, the job description closely parallels a set of workers already on the job at some healthcare institutions, private insurers and public health authorities: community outreach workers. Every day these workers pursue a community-based variant of what healthcare policy analysts call population health management.

Healthcare community outreach workers scour specific neighborhoods or targeted groups (such as hospital employees or a managed care organization’s “covered lives”) for people with untreated chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension and asthma. Some workers focus on cancer screening, or meeting women who need pre- and post-natal care.

In addition to getting people access to healthcare, community outreach workers – like tracers – seek to address the social determinants of ill health that leads to the higher incidence of these chronic conditions in the targeted communities. Very often that entails providing people food or housing through government programs or private charities. Community outreach workers need to work closely with the agencies that address behavioral health, substance abuse and obesity disorders, the petri dishes for the chronic disease epidemics plaguing America.

INVEST NOW OR…

The Trump administration has so far refused to coordinate a national tracing program. The states pursuing the strategy, already cash-strapped from the sharp decline in economic activity, are relying on funding from the emergency Cares Act. The stimulus bill allocated $631 million to state and local health departments for all surveillance programs, including tracing. That level of funding is inexplicably inadequate. The U.S. economy, ravaged by the world’s worst response to the COVID-19 pandemic, is hemorrhaging trillions of dollars in lost activity. The return from investing in a comprehensive testing and tracing program that enabled the full reopening of the economy would make a venture capitalist drool.

According to the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, it will cost a mere $3.6 billion to hire 100,000 tracers – the lowest estimate for how many will be needed for a nationwide, comprehensive program. The highest estimate would cost around $10 billion, still a rounding error in the Cares Act even though it is 15 times the original allocation.

But even if Congress increases funding for tracing in another stimulus bill, replicating the structure of the current program – short-term and limited to fighting COVID-19 – would be a tragic error. When the pandemic subsides and the fiscal stimulus expires, strapped state and local governments will lay off those temporary workers, most of whom will move back to employment in other industries. Local communities will lose their training and experience. It makes no sense to dismantle our ability to respond rapidly to pandemics. That’s what happened to the preparedness programs launched after the post-9/11 anthrax scare and the SARS, Ebola and MERS outbreaks of the past two decades. As federal grants dried up, state and local health departments eliminated 56,000 positions over the past decade, including most workers involved in pandemic response. [3]

We can do better. The federal government should make the tracing program permanent, just as it made the airport screeners run by the Transportation Security Administration permanent after 9/11. An annual $8 billion appropriation, roughly equivalent to what the TSA spends, would be sufficient to hire, train and retain a permanent corps of nearly 200,000 community outreach workers.

During “normal” times, that is to say most of the time, community outreach workers would serve as the leading edge of a coordinated attack on the nation’s most pressing public health problems: the chronic disease, opioid, behavioral health and obesity pandemics. During a disease outbreak, they would make up the pandemic preparedness corps that switches to emergency service as testers and tracers. A permanent pandemic preparedness corps will act like a public heath fire department.

When the next infectious disease pandemic hits, this corps will answer the call the way a fire department responds to a five alarm fire. The rest of the time, their primary goal will be reducing and preventing chronic disease, which is disproportionately concentrated in the nation’s poor and minority communities. The pandemic preparedness corps will become the institutional embodiment of a far-reaching program to address the social determinants of health.

CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

There is growing bipartisan support for rebuilding the nation’s infrastructure. The forthcoming legislation should include permanent funding for a pandemic preparedness corps.

The reasoning is simple. The future economic well-being of our society depends just as much if not more on the health and education of its workforce as it does on the condition of its roads and bridges. Earmarking $80 billion in a 10-year, $1 trillion infrastructure bill will be a wise long-term investment in improving the population’s overall health. Let’s consider the validity of the three main arguments against launching a comprehensive public health approach to combating chronic disease.

- Prevention doesn’t pay because it doesn’t reduce costs in other parts of the healthcare system.

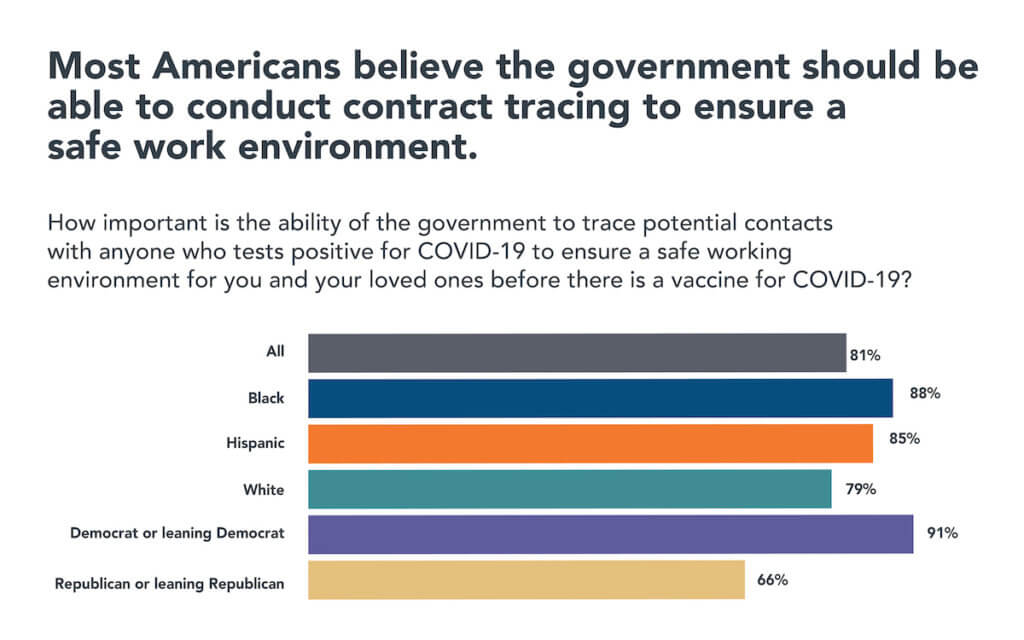

- People will not accept massive government intrusion into their private lives in the name of either pandemic response or improving population health.

- Government is incapable of pulling it off. It will wind up as just another failed anti-poverty program.

Let’s take each of those arguments in turn. First, most researchers who have evaluated the financial benefits of preventive medicine conclude most interventions do not reduce overall healthcare spending. [4] One study found only vaccinations and aspirin actually saved money. But this research only took clinical interventions into account. A National Business Group on Health study, cited in the same research, found that many social interventions do save money through the elimination of other healthcare spending. Cost-effective interventions included hypertension screening and treatment; alcohol and tobacco screening and counseling; and parental auto-safety counseling. [5]

Moreover, many social interventions like screening for undiagnosed pre-diabetes and diabetes, when coupled with counseling and treatment, improved life expectancy at a cost well below the cost of treating complications after the disease has advanced. A comparative cost-effectiveness lens magnifies the benefits of prevention. [6]

A handful of health systems are proving community outreach not only works, but generates positive economic returns. For nearly two decades, Mt. Sinai’s Urban Health Institute (SUHI) in Chicago has sent community outreach workers into some of the neighborhoods to screen for diabetes, asthma and breast cancer. With 10 outreach workers on its payroll now, SUHI hopes to expand to 50 workers by participating in the city’s nascent COVID-19 tracing program.

SUHI did a detailed cost-benefit analysis for its asthma program, which helps families by arranging home improvements and ensuring stricken children are properly treated. “There’s a huge economic impact,” says Helen Margellos-Anast, president of the institute. “We save $5 in direct healthcare costs for every dollar spent on the program. If you include indirect benefits like kids being in school and parents being able to go to work, it’s even greater.”

The second objection – that people will not accept public health intervention in their lives – can be addressed by hiring workers from the local community. Mt. Sinai’s programs, like all successful social interventions, hire and train local residents. People, especially those in low-income and minority communities, will accept intrusive public health measures when they see these “officials” are physically and culturally part of their community.

Source: Sara R. Collins et al., An Early Look at the Potential Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Health Insurance Coverage (Commonwealth Fund, June 2020).

SUHI uses a selective hiring process. It looks for people, even if only high school graduates, who want to enter the caring professions and are culturally, racially and economically similar to those that need the help. “They are able to connect with people in a very real way because they’re from that community. They’re trusted,” Margellos-Anast says. “Given all the tensions we have right now, that’s critical. That’s the only way this is going to be successful.”

Skeptics argue there is something innate in the American character that resists public health authorities from playing a more active role in preventing disease. It doesn’t matter whether government outreach is aimed at curbing the spread of COVID-19 or reducing America’s chronic disease epidemic, which affects about 42% of the population. [7]

A despairing population health proponent asks, “If people don’t wear a mask, which is such a basic, basic thing, do you think they’ll be forthcoming in a contract tracing interview?” This proponent works at a major academic medical center and does not wish to be identified. He continues, “It’s rugged individualism. We’re on the covered wagon heading for the Rocky Mountains and I’ve got my Winchester. That’s how we are.”

But America also has a barn-raising tradition, where people in the community come together to help neighbors in need. It has also embraced large government interventions when faced with crises like economic collapse, environmental degradation or racial discord. Recent public opinion polling in the wake of the George Floyd murder in Minneapolis shows increasing supporting for the Black Lives Matter movement. We may be nearing another such a moment.

Do these community-based organizations want the job? Yes, they will be whole-hearted supporters. But many hospitals, still wedded to fee-for service reimbursement, are reluctant to take on community-based population health challenges that involve minority and low-income communities. Medicaid doesn’t pay as well as commercial insurance, and hospital chief financial officers do not believe spending money to address the social determinants of health will show a return on investment. Permanent grant funding might overcome those objections.

To sum up, investing in improving population health will pay off for our entire society. People will accept public intervention in their lives in the name of public health if it is delivered by people recruited locally with the cultural sensitivity needed to work in the most affected communities. And federal funding channeled through local governments and their contractors, including non-profit agencies and institutions, will keep the new program true to its mission.

PREVENTION: AN ALMOST INFINITE RETURN ON INVESTMENT

The U.S. has paid an enormous price for its failure to adhere to the public health measures that experts recommend for controlling a deadly pandemic where there’s neither effective treatment nor a vaccine. Had the government heeded warnings from countries like Italy, which on April 1 had three times the deaths registered in the U.S., nearly 100,000 American COVID-19 victims would be alive today. If the economy could reopen like in Europe, tens of millions of Americans would be returning to work instead of remaining unemployed. [9]

As noted above, a mere $10 billion investment could have prevented this disaster. The economic return on investment would be measured beyond 10,000%. Until the U.S. makes that investment, its economy will continue to suffer incalculable damage.

The time to act is now. The federal government needs to include in either its next stimulus bill or an infrastructure bill (both under consideration in Congress) a permanent pandemic preparedness corps that doubles as a population health improvement corps. The authorizing legislation should give states the flexibility to adopt models that best fit their local conditions. The federal government can distribute the funding to the states on a per capita basis, and let the states establish structures that are best suited to their communities. Some public health departments remain well-run and well organized, even as others see seasoned professionals flee office due to evaporating support from their elected leaders.

The better-run states have the management skills needed to coordinate the healthcare providers, payers, clinicians, social service agencies and private charities that must be part of any successful program.

Other states or regions may want to rely on private contractors to run their pandemic preparedness corps. These could include hospital systems, managed care health plans, federally qualified health centers or large primary care practices.

Some may use a mix of the two approaches. The people on the ground are in the best position to know.

The real problem is summoning up the political will to tackle the most serious health challenges our society faces: the utter lack of pandemic preparedness; the chronic disease epidemics that are devastating minority and low-income communities; and the unaddressed social determinants of health that are driving those epidemics.

Americans understand their government badly bungled its response to COVID-19. They are outraged about the senseless police murders of African-Americans. A seismic shift in public opinion is underway. The latest polls show voters back new programs to address the social determinants of health and the glaring disparities in health outcomes. A permanent pandemic preparedness corps, which addresses both problems, should be high on lawmakers’ agenda.

SOURCES

- See https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html (accessed June 14, 2020).

- Simmons-Duffin, “As States Reopen, Do They Have The Workforce They Need To Stop Coronavirus Outbreaks?” (https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/06/18/879787448/as-states-reopen-do-they-have-the-workforce-they-need-to-stop-coronavirus-outbre, accessed June 18, 2020).

- Trust for America’s Health, “The Impact of Chronic Underfunding on America’s Public Health System: Trends, Risks and Recommendations 2020,” (https://www.tfah.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/04/TFAH2020PublicHealthFunding.pdf, accessed June 16, 2020).

- Aaron E. Carroll, “Preventive Care Saves Money? Sorry, It’s Too Good To Be True,” New York Times, Jan. 29, 2018 (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/29/upshot/preventive-health-care-costs.html, accessed June 15, 2020).

- Sarah Goodell, et al, “Cost Savings and Cost-Effectiveness of Clinical Preventive Care,” Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s The Synthesis Project, September 1, 2009 (https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2009/09/cost-savings-and-cost-effectiveness-of-clinical-preventive-care.html, accessed June 15, 2020).

- William H. Herman, “The cost-effectiveness of diabetes prevention: results from the Diabetes Prevention Program and the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study,” Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology, September 2015 (https://clindiabetesendo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40842-015-0009-1, accessed June 15, 2020).

- Christine Buttorff, et al, “Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States,” Rand Corporation, 2017 (https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/tools/TL200/TL221/RAND_TL221.pdf, accessed June 15, 2020).

- Source: Sara R. Collins et al., “An Early Look at the Potential Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Health Insurance Coverage,” Commonwealth Fund, June 2020. (https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jun/implications-covid-19-pandemic-health-insurance-survey, accessed June 25, 2020).

- On April 1, Italy suffered its worst day in the pandemic with 5,347 new cases, 727 deaths and a cumulative death total of 13,155. That same day, the U.S. reported 14,685 new cases, 331 deaths with a cumulative death total of 4,757 in a population about five times higher than Italy’s. As of On June 24, Italy had a total of 34,678, about three times its April 1 total. The U.S. death total that day was 122,370. Had the U.S. taken the same shelter-in-place and lockdown measures that Italy took around April 1, its death total would have been limited to about 15,000 and over 100,000 lives would have been saved.