May 1, 2017

40 Years in the Payment Reform Wilderness: DRGs to Nirvana

Introduction

| In an ideal state, a well-functioning healthcare delivery system should provide the right care at the right time and the right place, while being accountable for clinical and financial outcomes. |

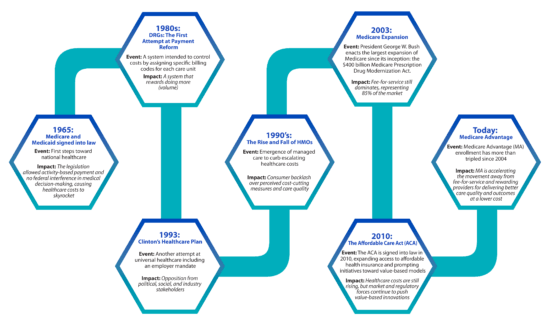

When President Lyndon Johnson described Medicare and Medicaid as he signed the sweeping new legislation in 1965, he painted a lofty picture of a system that would support effective healthcare for those in need in a land bursting with abundance.

Unfortunately, the reality of American healthcare in the subsequent years is much different. An uncoordinated delivery system provides fragmented, high-cost care. Outcomes are sub-optimal. Patient needs aren’t being met. Unpaid medical expenses are the leading cause of personal bankruptcy.

As a result of structural flaws to Medicare’s payment system, spending quickly spun out of control. Medicare spending ballooned more than 15 times from roughly $5 billion in 1967, Medicare’s first full year of operation, to $76.8 billion in 1986. By the mid-1980s, American healthcare had become big business.

Leavitt predicted that the pace of payment reform would accelerate in the last 10 to 15 years of this 40-year journey. Specifically, that this pace and structural change would put increasing pressure on industry incumbents clinging to fee-for-service payment models.

The acceleration toward value-based care is exactly what healthcare is experiencing today. What was a principal catalyst of this shift to value-based care delivery? The redesign of the Medicare Advantage program in 2003.

In an ideal state, a well-functioning healthcare delivery system should provide the right care at the right time and the right place, while being accountable for clinical and financial outcomes. With shared surplus and quality metrics at the core of its innovation, Medicare Advantage is a promising development in making value-based care work.

The 1960s: Medicare’s Original Flaws

When President Johnson brought Medicare and Medicaid to life in 1965, it marked the beginning of America’s experiment with national health insurance. Under Medicare, the percentage of America’s seniors with health insurance has grown from under 50 percent to 96 percent in 2009.[i]

| Medicare’s original flaws in 1965:

1: Activity-based payment structure 2: No federal interference in medical decision-making |

Despite Medicare’s successes, President Johnson made two major (and detrimental) concessions (Medicare’s original flaws) in order to ensure legislative passage.

The first flaw was agreeing to activity-based payment. Despite discussion about value-based reform, fee-for-service and the negative practices it engenders still dominate.[ii]

The second flaw was agreeing to no federal interference in medical decision-making. If doctors could justify medical treatments, Medicare, Medicaid and, by extension, commercial health insurers must pay for those treatments.

Fifty years later, this artificial payment model has created enormous distortions in healthcare’s supply and demand relationship. Patients routinely undergo unnecessary medical tests, treatments and procedures. Care delivery is fragmented, overly complex and uncoordinated, leading to poor outcomes, higher costs and patient dissatisfaction.

These original flaws have also led to a severe underinvestment in prevention, behavioral health, chronic disease management and health promotion. The result is an extremely high-cost healthcare system that treats byproducts rather than the root causes of disease and achieves suboptimal health outcomes.

At best, the current system invites manipulation through its payment mechanisms. At worst, it tolerates massive fraud, in many cases caught well after the occurrence as some providers put profits before patients. Much of the skyrocketing healthcare costs over the past five decades can be traced back to those two flaws baked into the original Medicare legislation.

The 1980s and 1990s: A Focus on Controlling Costs

DRGs: The First Attempt at Payment Reform

With costs accelerating at 1 to 3 percent more than general inflation, healthcare began consuming an ever-larger percentage of the national economy and federal budget. Medicare costs grew an average of 19 percent annually from 1979 to 1982.[iii]

To keep Medicare from insolvency, elected leaders turned to an alternative reimbursement system in the early 1980s: prospective payment with Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs).

| Diagnosis-Related Groups, or DRGs, are specific billing codes for inpatient care used to identify the price for specific treatments in different markets across the country—a first attempt by the federal government to control healthcare costs in the 1980s. |

This was the first real attempt by the federal government to control healthcare costs. DRGs are specific billing codes for inpatient care, including all diagnostic tests and procedures related to inpatient stay, which the government uses to identify the price it pays for specific treatments in different markets across the country. Rather than paying the hospital for what it spent caring for a hospitalized patient, Medicare pays the hospital a fixed amount based on the patient’s DRG or diagnosis. DRGs control the costs of every care unit—from an aspirin to a complicated surgical procedure.

Medicare officials hoped this payment system would encourage hospitals not to over utilize medical resources. Unfortunately, this approach was not enough. The reality is that the system rewards doing more (volume) rather than whatever would be the best, most appropriate course of care (value).

Code-based reimbursement systems expanded from Medicare and Medicaid to private payers, and eventually became the default systems for paying for nearly all of healthcare.

The DRG system initially did help hold down Medicare hospital costs. But many stakeholders soon learned how to increase revenue by optimizing the coding system. They began doing more of what gets better reimbursement, less of what does not, and making sure every item gets coded and charged. This code-based fee-for-service payment system is still going strong today.

Clinton’s Healthcare Plan of 1993

Concerns over medical inflation continued to mount in the early 1990s. Having campaigned heavily on healthcare reform, then President Bill Clinton set out to devise a universal healthcare plan, and appointed First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton head of the Task Force on National Health Care Reform.

Many at the time were unhappy with the healthcare system in the United States, where the cost of health insurance seemed increasingly unaffordable for the middle class. During this period, over 37 million Americans were completely without health insurance.

| The Clinton plan’s core element in the 1990s was for employers to provide health insurance coverage through competitive, but closely regulated, health maintenance organizations. However, political opposition prevented the bill’s passage. Healthcare reform would have to wait. |

The Clinton plan’s core element was an enforced mandate for employers to provide health insurance coverage to all of their employees through competitive, but closely regulated, health maintenance organizations (HMOs).

Opposition to the reform plan was heavy from conservatives, libertarians and the health insurance industry. Adding to the plan’s challenges, Democrats offered a number of competing plans of their own, rather than uniting behind the former president’s proposal.

Opposition forces ultimately prevailed. Despite large majorities in the House and Senate, Democrats were unable to produce a consensus bill. The air went out of the reform balloon. Running against big government, the Republicans behind Newt Gingrich and his “Contract with America” took control of both chambers in the 1994 mid-term elections. Healthcare reform would have to wait.

The Rise and Fall of Managed Care

After the failure of the Clinton administration to enact national healthcare reform, managed care expanded rapidly in the United States during the 1990s. Through physician gatekeeping and preauthorization mechanisms, managed care plans did succeed in curtailing runaway healthcare costs, particularly hospital utilization, a major source of expense.

| Managed care expanded rapidly in the United States during the 1990s, and while it did succeed in controlling costs, public outcry against quality of service prompted the establishment of managed care standards. |

The proportion of employees in managed care plans grew from five percent in 1984 to 50 percent in 1993.[iv] The expansion of managed care in the private sector was paralleled by increased adoption of this approach by public payers, fueled in part by the introduction of “flexible” health plans. Enrollment in Medicare managed care, which had remained at about 1 million between 1985 and 1991, increased to more than 6 million by 1999.[v]

Eventually, however, benefit denials and disallowances of medically necessary services prompted a public outcry and the enactment of laws in many states establishing managed care standards.

Whatever its failings, managed care did succeed in controlling costs. Between 1993 and 1998, healthcare costs increased 31 percent, a rate that was slower than any period over the last 40 years.[vi] When employers moved away from managed care, costs skyrocketed; between 1999 and 2010, healthcare costs more than doubled, increasing by 102 percent.[vii]

2000 – Present: A Focus on Access, Cost and Quality

Medicare Drug Expansion and the Affordable Care Act

| The Medicare Prescription Drug Modernization Act in 2003 added prescription drug benefits for Medicare beneficiaries and provided billions of dollars in subsidies to allow private plans to compete with Medicare. |

In the largest expansion of Medicare since its inception, President George W. Bush signed into law a $400 billion Medicare Prescription Drug Modernization Act in 2003. In addition to the prescription drug benefits, the measure provided billions of dollars in subsidies to insurance companies and HMOs, and took the first step toward allowing private plans to compete with Medicare.

Just a few years later, then Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney’s healthcare insurance reforms laws passed in Massachusetts. Known as RomneyCare, the plan provides health insurance to those who cannot afford it through subsidies. RomneyCare is still in effect and became the blueprint for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) due to its widely recognized success within Massachusetts.

In 2010, with only Democratic support, Congress passed the ACA, initiating the most sweeping changes in the U.S. healthcare system since Medicare inception. The ACA aimed to greatly increase the number of Americans who have access to affordable health insurance by establishing a standardized benefits package, pricing parameters and full eligibility (i.e., no exclusions for people with pre-existing medical conditions).

| The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 initiated the most sweeping changes in the U.S. healthcare system since Medicare’s inception. |

From its 2013 launch, the ACA rollout was bumpy, due to technical glitches and web outages affecting the federal Healthcare.gov website. Despite the poor rollout, the number of enrollees in healthcare plans under the law exceeded the Obama administration’s target of 7 million people its first year and continued to expand in subsequent years.

The ACA has increased access and costs did moderate for a period of time. Many economists attribute lower healthcare spending to the recession that took hold in 2008, not to Obamacare. Healthcare costs are now rising faster than inflation again – up 5.8 percent in 2015 to $3.2 trillion. And, after the Trump administration’s recent failure to repeal and replace the ACA, the landmark healthcare law remains in effect for the foreseeable future.

Well into the 21st century, efforts to control healthcare costs have largely failed. Despite reform initiatives aimed at shifting to value-based payment models, fee-for-service still dominates, with 86 percent of physicians still reporting being compensated in traditional fee-for-service or salary compensation models.[viii]

The stakes have never been higher to reduce costs and improve quality and outcomes, which means a shift to value-based payment models is inevitable. But the only way to get there is through a fundamental shift in thinking.

Medicare Advantage: A Model That Delivers on Value

Since the 1970s, seniors have had the option to receive their Medicare benefits through a private health insurance plan instead of through traditional Medicare. It started out so that patients enrolled in HMOs, like Kaiser Permanente, could keep their doctors. As policy makers began favoring managed care as a way to control healthcare costs, private Medicare plans took off.

The program became known as Medicare Advantage (MA) when Congress passed the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. The modernization incentivized greater access to MA by providing extra payments to insurers offering these plans. The law also required insurers to share the benefits of these payments with enrollees in the form of additional payments or lower premiums.

| Today, Medicare Advantage is accelerating the movement toward value-base care with its quality metrics and bonuses, patient-centered medical home initiatives, and other efforts that reward value versus volume. |

The payment policy shifted again with the passage of the ACA in 2010, reducing federal payments to plans over time, bringing them closer to the average costs of care under the traditional Medicare program. It also provided bonus payments to plans based on quality ratings.

Since 2004, the number of beneficiaries enrolled in private MA plans has more than tripled, from 5.3 million to 17.6 million in 2016.[ix] The reason for MA’s growing popularity? Many seniors find that MA plans better meet their needs and desires for coverage. These plans offer supplemental benefits, such as vision, dental and hearing coverage, as well as out-of-pocket maximums.

Unlike traditional Medicare, private MA plans have the flexibility to provide innovative care coordination for chronic conditions and preventive care programs to meet patients’ needs. That translates to improved health status and reduced unnecessary hospitalizations.

One study found that intensive office-based care for a group of MA members with multiple comorbidities reduced hospital-based care compared to a control group of traditional Medicare program enrollees. This change in utilization saved well over $2 million per 1,000 enrollees. In addition, by intensifying office-based care for these MA enrollees, a 32.8 percent lower hazard of death was achieved.[x] As the Medicare-eligible population continues to grow—increasing by almost 50 percent by 2030 to over 80 million beneficiaries—the need for effective value-based population health management becomes inevitable.[xi] Healthcare organizations will need a long-term business strategy to successfully manage their Medicare population—and a value-based MA strategy can provide that option.

MA is accelerating the movement toward value-base care with its quality metrics and bonuses, patient-centered medical home initiatives, and other efforts that reward value versus volume. Under MA programs, health plans and doctors are accountable for the total cost of care—MA plan providers are as concerned about their members’ health outside their clinic walls as well as inside them.

Disruption, Thy Name is Medicare Advantage

MA is a powerful force in transforming the current U.S. healthcare system away from fee-for-service reimbursement to payment for value-based care delivery. Forward-thinking organizations understand that the time to adopt a patient-centered, value-based system is now. Provider and payer organizations that continue to deliver fragmented, inefficient care risk losing market relevance.

In short, MA is the most powerful lever the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has to shape the future of healthcare and overcome Medicare’s fatal flaws.

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll highlight Medicare Advantage’s success in delivering better healthcare at lower costs in patient-friendly venues.

About the Authors

Dave Johnson

David Johnson is the CEO of 4sight Health, a boutique healthcare advisory and investment firm. Dave wakes up every morning trying to fix America’s broken healthcare system. He is a frequent writer and speaker on market-driven healthcare reform. His expertise encompasses health policy, academic medicine, economics, statistics, behavioral finance, disruptive innovation, organizational change and complexity theory. Dave’s newly published book, Market vs. Medicine: America’s Epic Fight for Better, Affordable Healthcare, is available on www.4sighthealth.com

Gaurov Dayal

Gaurov Dayal, M.D., is a versatile leader responsible for the nationwide adoption of Lumeris’ Population Health Services Organization (PHSO) solutions by the industry’s leading health systems. He offers deep knowledge and a unique perspective on health systems, the largest and fastest growing segment of the population health market, through his executive experience at top healthcare organizations, such as SSM Health and Adventist Healthcare. In his role, he oversees business development, key partnerships and revenue growth within health systems, while continually improving the reliability and effectiveness of Lumeris’ PHSO solutions for this emerging segment.

Jeff Smith

Jeff Smith is an established health care executive with 20 years of health care technology and pharmaceutical services experience in sales and account management, operations, product development and management, business development and corporate strategy. Earlier in his career, Jeff started a point-of-care software business that grew to a market leader. Immediately before joining Lumeris, he was vice president of Strategy, Acquisitions, and Population Health Management at CVS Caremark, one of the nation’s leading integrated pharmacy services companies. Jeff also served six years on the board of directors of RxHub and Surescripts. In his current role, Jeff is responsible for the national oversight of Lumeris’ sales, marketing, and advisory solutions.

[i] http://www.integratedcareresourcecenter.com/PDFs/ICRCReducingAvoidableHospitalizations%20508%20complete.pdf

[ii] http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/3/411.abstract. Retrieved March 2017.

[iii] Judith Mistichelli, “Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) and the Prospective Payment System: Forecasting Social Implications,” Cope Note 4, National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature, http://bioethics.georgetown.edu.

[iv] Jensen G. The new dominance of managed care: Insurance trends in the 1990s. Health Affairs. 1997;16:125–136. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.16.1.125. [PubMed]

[v] Gold M. Medicare + Choice: An interim report card. Health Affairs. 2001;20:120–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.4.120. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

[vi] CentersforMedicaidandMedicareServices.Nationalhealthexpenditures,Table 1: NHE Aggregate. https://www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads /tables.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2017.

[vii] 4. CentersforMedicaidandMedicareServices.Nationalhealthexpenditures,Table 1: NHE Aggregate. https://www.cms.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads /tables.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2017.

[viii] https://dupress.deloitte.com/dup-us-en/industry/health-care/physician-survey-value-based-care-models.html

[ix] CMS State/County Market Penetration Files, 2016

[x] Aloke K. Mandal, MD, PhD; Gene K. Tagomori, BSc; Randell V. Felix, BSc; and Scott C. Howell, DO, MPH&TM. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(2)

[xi] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/chapter-2-the-next-generation-of-medicare-beneficiaries-june-2015-report-.pdf?sfvrsn=0