May 21, 2025

Gas Stations and Hospital Prices

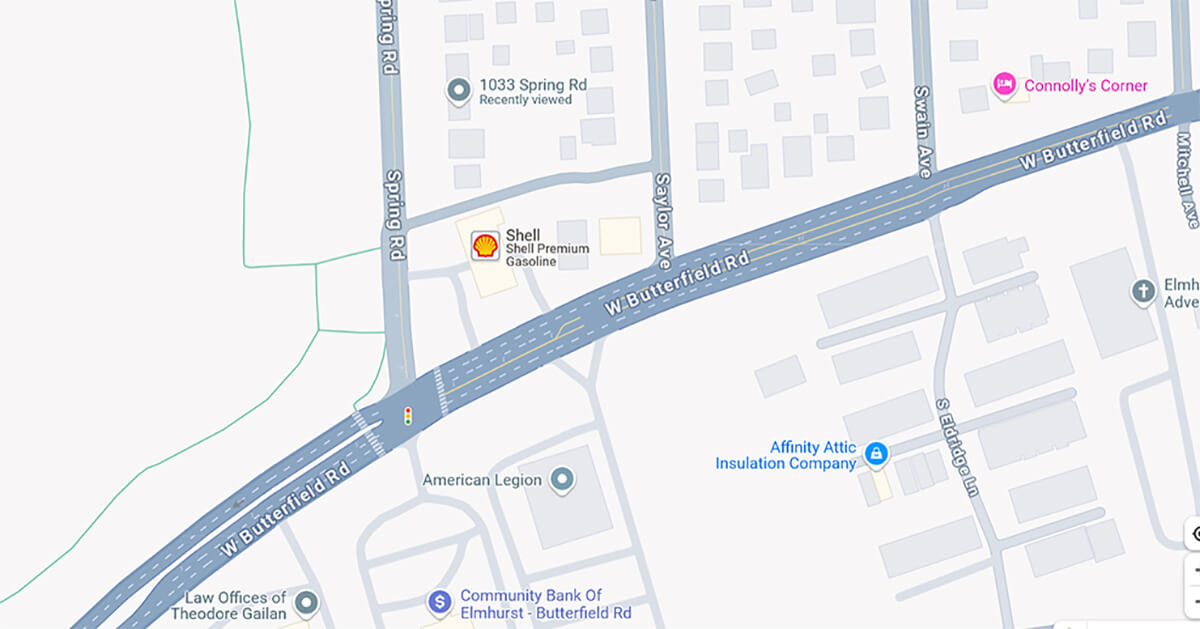

I drive through the intersection of Butterfield Road and Spring Road in Elmhurst, Illinois, all the time. It’s the fastest local route to get to my mom’s house. I attend a lot of events, functions and activities at Elmhurst University, my alma matta. And I have a good friend who lives near there, I go see him frequently.

On the northeast corner of that intersection is a small Shell gas station. The price it charges for a gallon of unleaded gas is always at least 20 cents higher than at any other gas station in the area. Always.

Why? Two reasons. First, it’s located at an important and busy crossroad. Go east, and you head toward Chicago. Go west, and you head toward the western suburbs. Go north, you head toward the university and downtown Elmhurst. Go south, it’s an endless sea of suburban homes. Second, it’s the only gas station two miles in any direction. If you’re going left, right or straight and you’re low on fuel, you better fill up there.

The lack of competition, combined with consumer need, enables the gas station to arbitrarily charge more for gas regardless of the prevailing price in the area. It charges more simply because it can.

A new study in Health Affairs says hospitals do the same thing, demonstrating once again that businesses in healthcare are like businesses in any other industry.

Two researchers from the University of Minnesota and the Health Care Cost Institute in Washington wanted to know how prices changed at “surviving” hospitals when nearby rural hospitals closed.

Their study pool included 54 rural hospitals that closed during a five-year period, 2014 through 2018, 150 “surviving” hospitals near the rural hospitals and a control group of 157 hospitals that mirrored the characteristics of the survivor hospitals.

Using claims data from commercially insured patients, they calculated an average annual price for an inpatient stay for the hospitals for the period 2012 through 2022. That allowed them to compare the prices charged by all the hospitals before and after each of the 54 rural hospitals closed. As a starter, they calculated that the average annual price for an inpatient stay at the rural hospitals in the study was 6% less than their three nearest and soon-to-be surviving competitors the year before they closed.

Here’s the good stuff. The researchers found that the average annual preclosure price for an inpatient stay at the three surviving hospitals rose 1.7% during the first two years after their nearby rural hospital competitor closed. It rose 6.3% in years three and four after the closure. The overall price hike during the study period was 3.6% with some interesting variations:

- It was 4.5% for surviving hospitals in less competitive markets.

- It was 4.4% for surviving hospitals affiliated with bigger health systems.

- It was 1.1% for surviving independent hospitals.

- And it was -1.8% for surviving hospitals in more competitive markets.

The researchers drew several conclusions from the results.

“Price effects were concentrated among surviving hospitals with market power — hospitals with system affiliations and hospitals operating in less competitive markets,” they said.

Further: “Closure eliminated low-price hospital options from rural markets.”

My conclusion is that the surviving hospitals raised their prices simply because they could. And the more they could, the higher the price increase.

No different from the Shell gas station at the corner of Spring Road and Butterfield Road in Elmhurst.

Tell me again that healthcare is different? I don’t think so.

Thanks for reading.

To learn more about this topic, please read, “Who Owns Rural Medicine?” on 4sighthealth.com.