May 20, 2025

Prevention Outperforms Treatment: Who Wins When We Stay Sick?

More than 250 years ago, Ben Franklin warned us: “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Today, that wisdom could rescue our healthcare system, or disrupt it entirely. As the American healthcare system buckles under financial strain, the surge in preventable chronic illnesses threatens to break it entirely. Yet, whole sectors of the industry profit from the status quo: more illness means more revenue.

What if we reversed the equation? Moving naturally, purposeful living, work-life balance, wholesome dietary choices, family, friends and social interaction have all been proven to decrease the need for and cost of healthcare. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) wisely states, “It is far better to prevent disease than to treat people after they get sick.” Avoidable chronic illnesses are associated with suffering, premature death and high health costs.

The cost gap between chronic disease and prevention is massive, and closing it could save both our healthcare system and our country. The CDC, with many others, has extensively studied and reported on the subject. [2]

Here’s the twist: Saving lives through prevention would disrupt the business of saving lives. The growth of self-induced chronic illnesses when combined with financial pressures will accelerate the downfall of an already barely sustainable healthcare industry. [1]

The Scope of the Problem

There’s a prevalence and disparity of chronic disease and inequity in America. Forty percent of Americans have at least one chronic illness. Eight of the Top 10 causes of death are due to a chronic disease. Obesity exacerbates the morbidity of other chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and some forms of cancer. [3] [4]

Concerningly, the prevalence of chronic disease is expected to increase over the next 25 years. “Consequently, by 2050, most individuals 50 years and older will have one or more chronic conditions,” according to a study published by Case Western Reserve University in 2023. [5]

Here is a bit of good news for optimistic folks who are playing the long game of living to age 90: “The progression from healthy to one chronic condition [shows] the transition rates begin to decrease significantly from age 90,” according to the same Case Western paper. People who believe they can live to 90 have a higher rate of success than those who don’t, according to a 2022 paper from the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. [5] [6]

The most affluent 1% of men lived 15 years longer than the poorest 1%. The gap for women is 10 years, which is the same number of years that smoking shortens life expectancy. Other nations do not depend on private health insurance, the lack of which results in about 45,000 people dying yearly because they cannot afford healthcare. Low-income adults are three times more likely than affluent adults to have trouble with activities of daily living such as eating, bathing and dressing. National financial crises typically exacerbate the disparities. [7] [8]

A Healthier Path Forward

There’s good news, too. Between 1980 and 2000, U.S. deaths from coronary heart disease dropped significantly. “Approximately half the decline in U.S. deaths from coronary heart disease from 1980 through 2000 may be attributable to reductions in major risk factors and approximately half to evidence-based medical therapies,” according to a 2007 New England Journal of Medicine paper. Risk factors showing improvement included decreased rates of smoking, reductions in total cholesterol, lowered blood pressure, and improved physical activity. These positives were partially offset by increased obesity and diabetes. [9]

The other half of cardiac mortality improvements resulted from open heart surgery, angioplasty and heart failure treatments. These noble medical and surgical advances save lives, but they’re costly and often come with side effects that prevention could avoid. Both prevention and treatment of cardiac disease are important and complementary. But prevention is so much less costly, efficient and effective. Emergency care saves lives, but avoiding the need for it is even better. Fire prevention trumps firefighting any day.

On a broader scale, entire regions ranging in size from almost 1 million to as small as tens of thousands have changed their culture along with other objective benefits. Southwest Florida embraced Blue Zones in 2015 and subsequently, during the next five years, added 0.6 years of life expectancy across a socioeconomically diverse population of almost 400,000. Medically self-insured organizations decreased their healthcare costs by about 50%. These organizations included a 725-bed, two-hospital healthcare system, the county’s employees and others as noted in a Feb. 13, 2018, New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst article. [10] [11]

Lower Costs, Stressed Providers

Imagine a world where prevention works so well, entire sectors of the healthcare economy become underutilized. The image that comes to mind is the Maytag repairman, the loneliest guy in town because the appliances never broke.

If 80% of chronic illnesses were prevented, five major healthcare sectors would feel the pinch:

- Physicians and Advanced Practice Providers

- Hospitals and Health Systems

- Pharmaceutical Companies

- Device Manufacturers

- Health Insurance Companies

These industries depend on a steady flow of sick patients. A healthier society would force a complete economic rethink, one that puts wellness over treatment.

We’ve seen this before: When medicine wins, the system must evolve. Just as polio vaccines and fluoride transformed public health, large-scale prevention today would demand a new healthcare model.

We’ve seen this before: When medicine wins, the system must evolve. Just as polio vaccines and fluoride transformed public health, large-scale prevention today would demand a new healthcare model.

Times change. Prevention helps patients, but it also disrupts the healthcare economy, creating winners and losers. Consider a few of the Top 10 medical miracles of the last century such as polio vaccine, antibiotics and fluoride. Esteemed hospitals rebranded themselves, changing names like Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled to Hospital for Special Surgery. Tuberculosis sanitariums became mountain resorts in the Adirondacks with the introduction of Isoniazid (INH), an effective treatment for TB. The incidence of dental decay in children dropped significantly in regions with fluoride in the water. [12]

The Science Supporting Prevention

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force addresses over 90 topics and is considered the gold standard in preventive care. The final evidence-based recommendations are developed from initial suggestions from anyone in the public, whether a professional or not, for review. These nominations are judged for relevance and impact and, if accepted, transformed into a research plan. Public comment is encouraged, followed by a finalized research plan. Researchers post the results for public comment before publishing them in a peer-reviewed journal. An educational graphic can be reviewed at USPSTF Recommendations Development Process: A Graphic Overview. [13] Final recommendations are graded “A” through “D” or “There is not enough evidence to make a recommendation.”

Benefits of Wellness vs. Illness

Specific cost savings with prevention are numerous. “Clinical preventive strategies are available for many chronic diseases; these strategies include intervening before disease occurs (primary prevention), detecting and treating disease at an early stage (secondary prevention), and managing disease to slow or stop its progression (tertiary prevention).” [14]

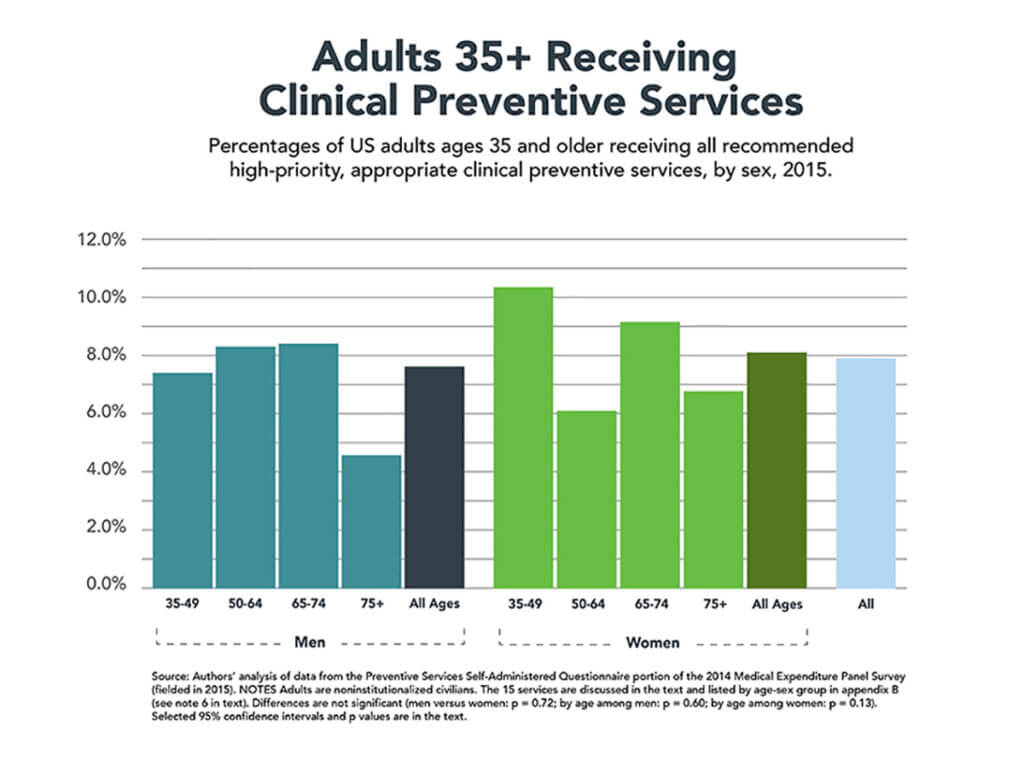

Evidence tools, including lifestyle changes, early detection and prompt effective treatment, have been shown to decrease misery and cost. In 2015, only 8% of U.S. adults 35 and older received all recommended, high-priority, appropriate clinical preventive services and nearly 5% received none. [15]

One-third of the working population in the U.S. are obese, slightly less than 20% still smoke, and more than half do not meet physical activity recommendations. The CDC believes addressing these conditions is a winnable public health battle. [16] [17] [18]

Preventable causes of death, including tobacco use, poor diet, physical inactivity and alcohol abuse, are responsible for nearly 40% of all deaths. Moreover, avoidable deaths have increased in America from 2009 to 2021, while other developed nations generally showed improvement. [19] [20]

Avoiding absenteeism among employers with chronic diseases — hypertension and diabetes and risk factors — smoking, physical inactivity and obesity has been extensively examined. Employees with one of these conditions miss one or two more days per year. That costs employers about $16 to $81 annually for small employers, and $17 to $286 for large employers. Although these costs seem minimal, when they are added together for the entire country, the cost is greater than $2 billion. [21]

Additionally, many traditional interventions are cost-effective and should not be overlooked. Colonoscopy for 60- to 64-year-old men and childhood vaccines show the downstream savings more than pay the cost for the intervention.

Surprisingly, not everyone believes prevention is cost-effective as noted in a 2025 JAMA Health Forum paper. Their argument is that prevention comes with a cost that exceeds the cost of treatment. This is sometimes true. The goal is to avoid expensive, inefficient “fixes” and implement healthy, less expensive lifestyle behaviors. [22]

For prevention to succeed, it must cost less than treating the disease. And the prevention needs to be effective as measured by the number of people who need to embrace this behavior to avoid the disease. Epidemiologists call this, “The number needed to treat (NNT).” What is obviously missing is the misery associated with suffering unnecessarily from a preventable disease.

The Bottom Line

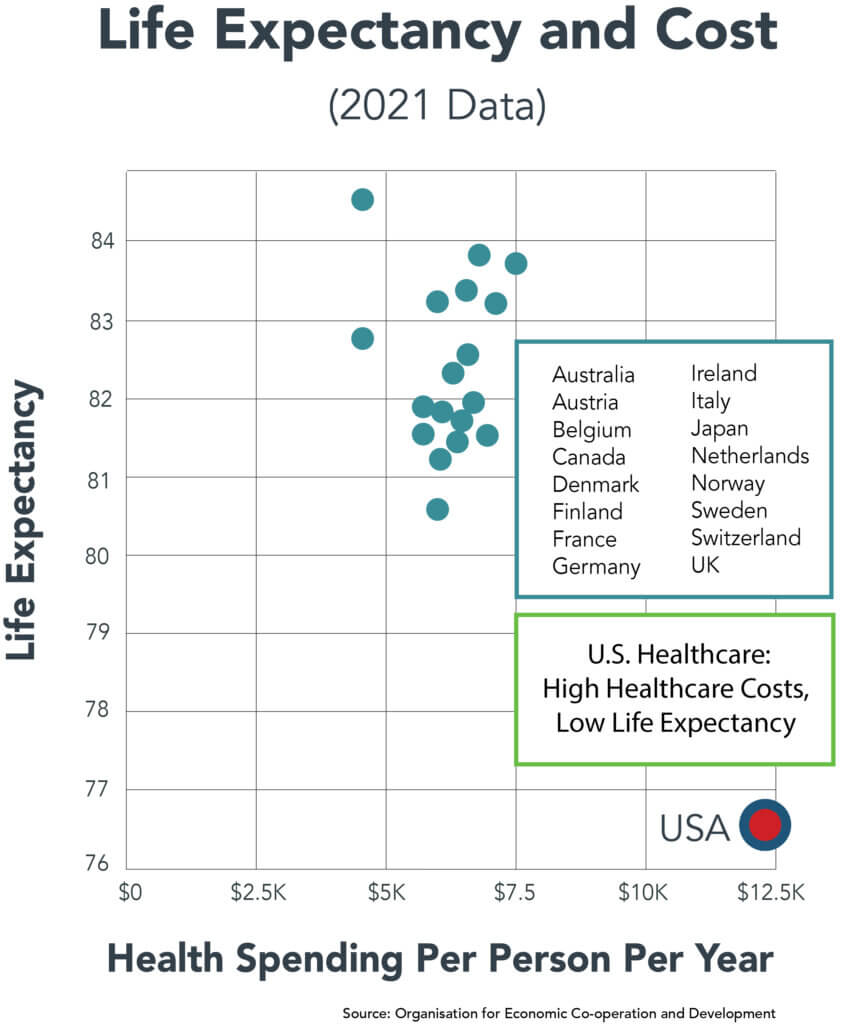

America spends more on healthcare than any other nation — with poorer outcomes to show for it. Prevention offers a practical solution: reduce the need for care by keeping people healthy in the first place.

Embracing prevention with an attractive, proven program for an organization, community or large region has lowered the cost and need for healthcare. As financial pressures grow, reducing healthcare’s share of our GDP must become a national priority. More medicines and rescue therapies or additional hospital beds and clinics are not the answer. Prevention by encouraging healthy lifestyles has already been shown to increase life span and wellbeing while being less expensive and more comforting.

Programs like Blue Zones prove that community-level interventions work. Roughly 75 U.S. communities are now using this model, serving 5 million residents across all income levels. These aren’t pilot projects — they are blueprints.

The future of healthcare doesn’t lie in more ICUs or miracle drugs. It lies in creating healthier communities. Let’s invest in the systems that prevent illness, not just the ones that profit from it.

Sources

- “An Ounce of Prevention Is Worth a Pound of Cure,” Words and Their Stories, Learning English, March 14, 2020.

- “Health Care Industry Insights: Why the Use of Preventive Services Is Still Low,” by Susan Levine, Erin Malone, Akaki Lekiachvilli, Peter Briss, Preventing Chronic Disease, CDC, March 14, 2019.

- “Chronic Disease Prevalence in the US: Sociodemographic and Geographic Variations by ZIP Code Tabulation Area,” by Gabriel Benavidez, Whitney Zahnd, Peiyin Hung, Jan Eberth, Preventing Chronic Disease, February 29, 2024.

- “How Has the Burden of Chronic Diseases in the U.S. and Peer Nations Changed Over Time,” by Telesford, Matthew McGough, Delaney Tevis, and Lynne Cottee, Health System Tracker, April 16, 2025.

- “Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model,” by John Ansah and Chi-Tsun Chiu, Frontiers in Public Health, January 13, 2023.

- “Optimism, lifestyle, and longevity in a racially diverse cohort of women,” by Hayami Koga, Claudia Trudel-Fitzgerald, Lewina Lee, Peter James, Candyce Croenke, Lorena Garcia, Aladdin Shadyab, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, October 2022.

- “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014,” by Raj Chetty, Michael Stepner, Sarah Abraham, Shelby Lin, Benjamin Scuderi, Nicholas Turner, Augustin Bergeron, David Cutler, JAMA, April 26, 2016.

- “Lack of Insurance to Blame for Almost 45,000 Deaths: Study, Atlanta Journal Constitution, September 17, 2009.

- “Explaining the Decrease in U.S. Deaths from Coronary Disease, 1980-2000,” by Earl S. Ford, Umed A. Ajani, Janet B. Croft, Julia A. Critchley, Darwin R. Labarthe, Thomas E. Kottke, Wayne H. Giles, and Simon Capewell, New England Journal of Medicine, June 7, 2007.

- “Why People in ‘Blue Zones’ Live Longer Than the Rest of the World,” by Ruairi Robertson, Healthline, December 3, 2024.

- “Decreasing the Cost of Care by Avoiding Illness,” by Allen Weiss, New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst, February 13, 2018.

- “Fluoridation cessation and children’s dental caries: A 7‐year follow‐up evaluation of Grade 2 schoolchildren in Calgary and Edmonton, Canada,” by Lindsay McLaren, Steven K Patterson, Peter Faris, Guanmin Chen, Salima Thawer, Rafael Figueiredo, Cynthia Weijs, Deborah McNeil, Arianna Waye, and Melissa Potestio, Community Dental and Oral Epidemiology, October 5, 2022.

- “USPSTF: The Primary Care Clinician’s Source for Prevention Recommendations,” U.S. Prevention Services Task Force, 2024.

- “Health Care Industry Insights: Why the Use of Preventive Services Is Still Low,” by Susan Levine, Erin Malone, Akaki Lekiachvili, and Peter Briss, CDC Preventing Chronic Disease, March 14, 2019.

- “Few Americans Receive All High-Priority, Appropriate Clinical Preventive Services, by Amanda Borsky, Chunliu Zhan, Therese Miller, Quyen Ngo-Metzger, Arlene Bierman, and David Meyers, Health Affairs, June 2018.

- “Prevalence and Trends in Obesity Among US Adults, 1999-2008,” by Katherine Flegal, Margaret Carroll, Cynthia Ogden, JAMA Network, January 20, 2010.

- “Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States,” Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2022.

- “Adult participation in aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activities — United States, 2011,” by CDC, Morbidity and Mortality Report, May 3, 2013.

- “Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000,” by Ali Mokdad, James Marks, Donna Stroup, Julie Gerberding, JAMA, March 10, 2004.

- “Avoidable Mortality Across US States and High-Income Countries,” by Irene Papanicolas, Maecey Niksch, Jose Figueroa, JAMA Internal Medicine, March 24, 2025.

- “Absenteeism and Employer Costs Associated with Chronic Diseases and Health Risk Factors in the US Workforce,” by Garrett Beeler Asay, Kakoli Roy, Jason Lang, Rebecca Payne, and David Howard, Preventing Chronic Disease, October 6, 2016.

- “Can Prevention Save Money?” by Katherine Baicker and Amitabh Chandra, JAMA Health Forum, April 3, 2025.