May 7, 2019

An Unbearable Burden (Part 2): Wide Variations in State Health Insurance Costs

The Healthcare Affordability Index (Index) is a simple and powerful metric for assessing the impact of rising healthcare cost on American living standards. The Index measures the relationship between the total cost (employer and employee portions) of a commercial family health insurance policy relative to Median Household Income (MHI).

Importantly, the Index reveals this obvious but hidden truth: the very high cost of private health insurance contributes significantly to middle-class wage stagnation. More than half of Americans depend on employer-sponsored health insurance for their healthcare.

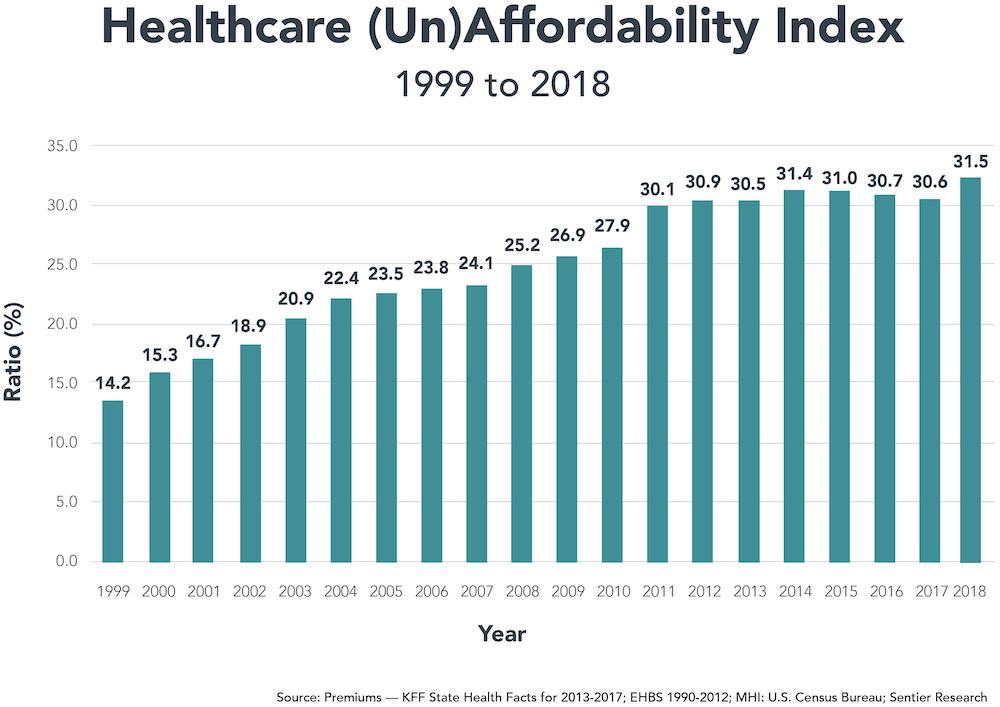

As health care costs rise, health insurance premiums also rise. This requires both employers and employees to pay more for healthcare coverage. Between 1999 and 2018, the cost of a family health insurance policy more than tripled from $5,791 to $19,616. These are alarming figures.

Source: Premiums — KFF State Health Facts for 2013-2017; EHBS 1990-2012; MHI: U.S. Census Bureau; Sentier Research

Since 1999, commercial health insurance premiums for families increased at 6.5% annually, more than triple the rate of general inflation (2.1%) and almost double the rate of healthcare inflation (3.5%). As a consequence, the healthcare industry has become increasingly dependent upon commercial insurance premiums to fund its increasing costs.

Part 1 of An Unbearable Burden examined the costs and implications of rising health insurance costs on average families. The Affordability Index more than doubled between 1999 and 2018 from 14.2 to 31.5, its highest level ever (see chart). In this Part 2, we examine state-specific Index scores. Their variation is breathtaking and heartbreaking. While all Americans bear the burden of increasing health insurance premiums, that burden falls disproportionately on lower-income communities and families.

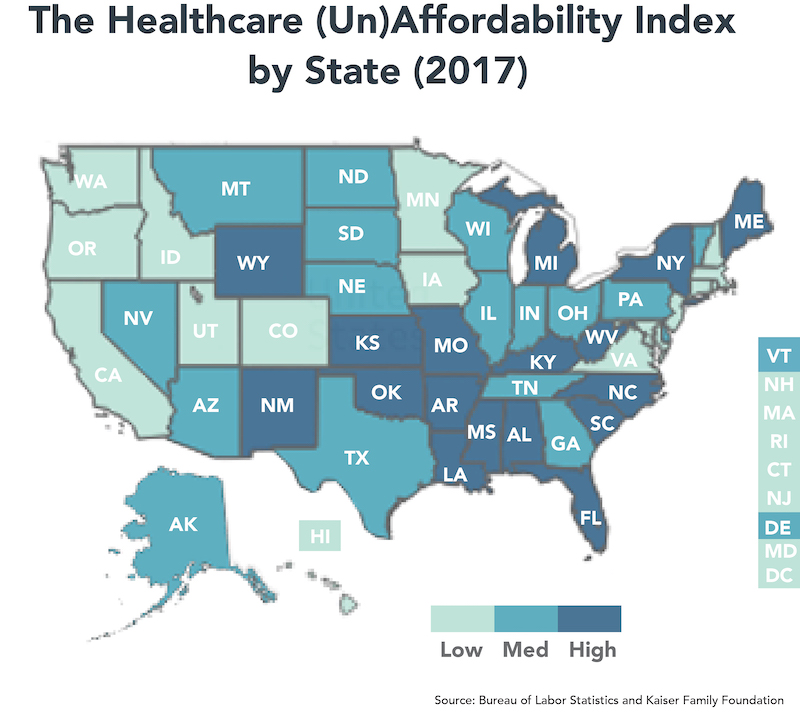

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Kaiser Family Foundation

Healthcare’s rising costs are an underappreciated component of the wage stagnation afflicting U.S. workers. Increasing health insurance premiums reduce monies available for wage increases. Life quality for average Americans diminishes as they struggle to pay for basic necessities while maintaining health insurance coverage.

State-Specific Healthcare Affordability

The state-specific Index scores vary dramatically from a low of 22.9 in Utah to a high of 44.6 in West Virginia. As described above, we calculate the Index by dividing total family health insurance premiums by median household income.

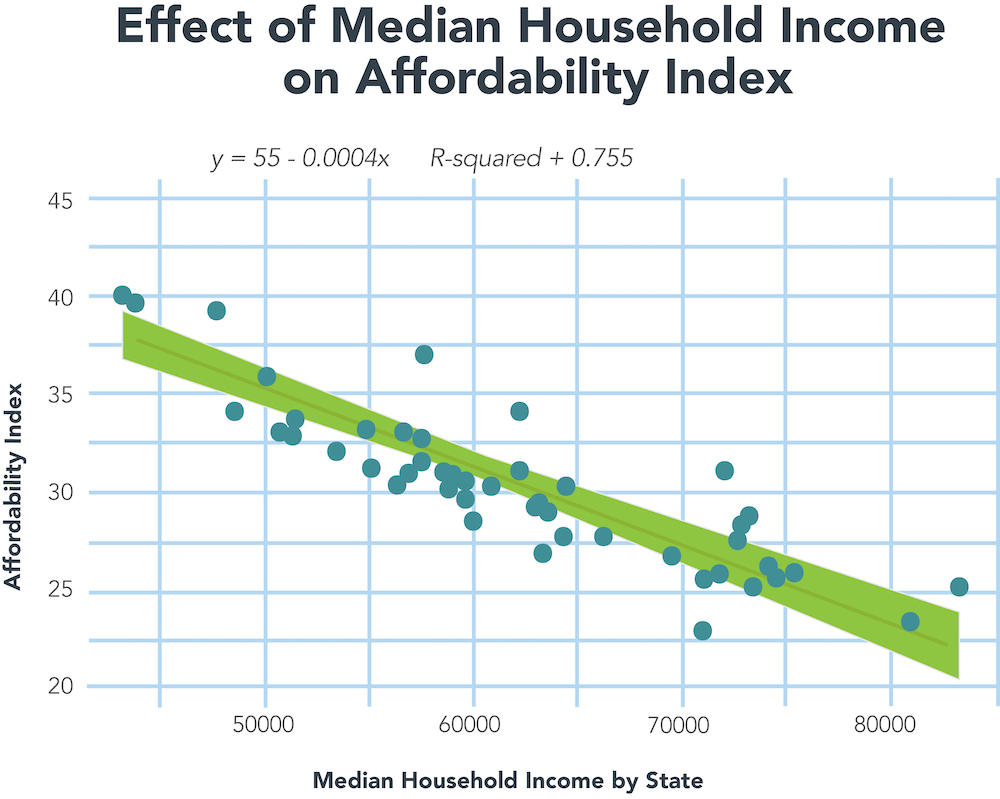

Of the two components, there is far greater variation in MHI than health insurance premiums. Washington D.C.’s MHI of $83,382 is almost double Mississippi’s MHI of $43,441. The high variation in MHI among states gives MHI much greater “weight” in explaining state-specific scores. MHI explains roughly 80% of an individual state’s ranking.

By contrast, the differential between the highest and lowest health insurance policies is only 37%. At $16,350, Utah’s average annual premium is the lowest. At $22,417, Alaska’s average annual premium is the highest. With significantly lower variation, total insurance premiums have less influence than MHI in calculating state-specific Index scores.

Here’s the rub. The lower a state’s Median Household Income, the higher the burden of paying for commercial health insurance.

This chart depicts the tight correlation between a state’s MHI and its Affordability Index.

The Affordability Index correlates inversely with Median Household Income. States with high Index scores have lower MHI and vice versa. The detail contained in the charts of the 10 highest and lowest Affordability Index affirms this conclusion. The two outlier states are New York and Wyoming. Ranked 22nd with $62,447 in MHI, New York achieves the 7th highest Affordability Index (34.1) because its residents pay very high health insurance premiums — $21,317 for an average family policy. This premium level ranks 3rd nationally. At $21,355, Wyoming residents pay even more for health insurance than New Yorkers. This propels Wyoming to the 5th-highest Index score.

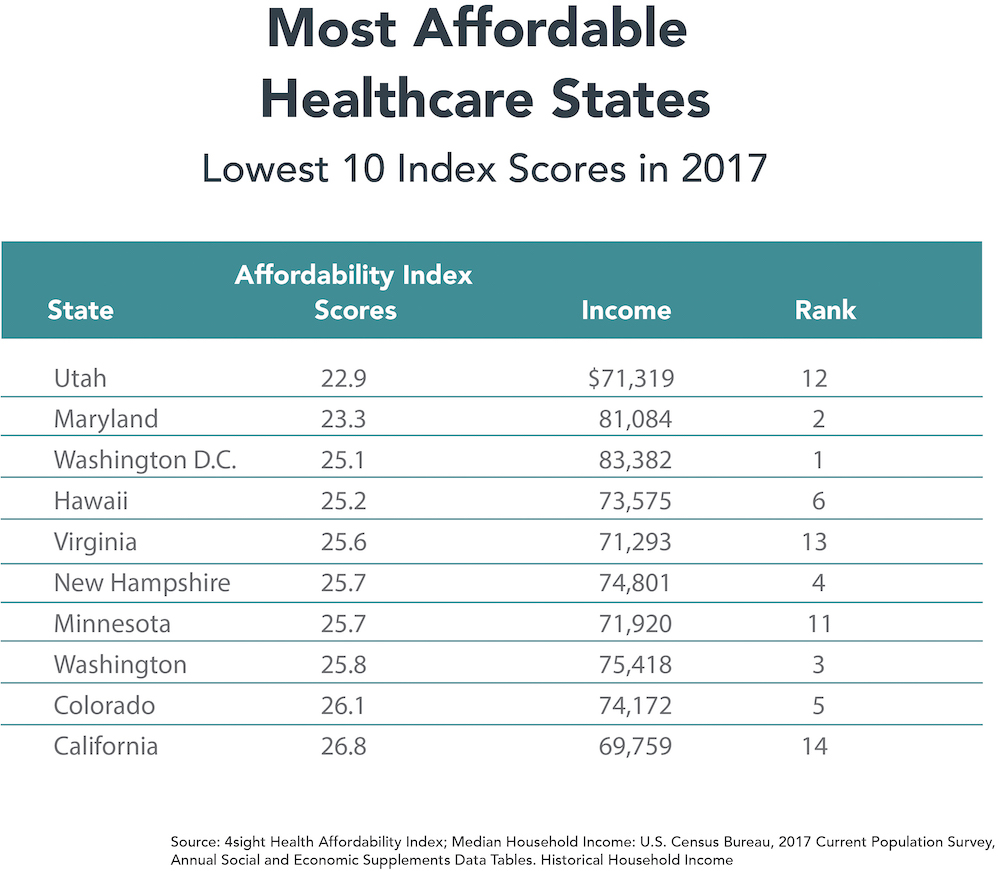

The 10 states with the lowest Index scores come from the group of 14 states with the highest MHI (see chart). The cost of health insurance policies within each state drive their relative rankings. States ranked 11-14 in MHI (Minnesota, Utah, Virginia and California) generated low Index scores because family health insurance in these states costs less than $18,750 annually versus the national average of $19,616.

States that ranked 7-10 in median household income (Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut and Alaska) did not qualify among the 10-lowest because health insurance in these states is expensive. Family health insurance policies in these states cost more than $20,000 annually.

Interestingly, the size of a state’s population and economy (as measured by state gross domestic product) had no correlation with Index scores. Scale doesn’t matter. The states with the second-, third- and fourth-largest populations and economies (Florida, New York and Texas) have below-average Index scores.

By contrast, several small states (Hawaii, Idaho, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Washington, DC) generate Index scores in the lowest third. With the exception of the Southeast, geography does not seem to predict Index scores. A high percentage of low income states with high Index scores concentrate in the Southeast.

Crueler Still: High-Cost Employee Premiums Predominate in Low-Income States

There also is remarkable state-specific variation in the percentage of the total health insurance premium paid by employees. Wisconsin is the lowest at 15.1%. Louisiana is the highest at 34.4%, more than twice the Wisconsin level.

Many low-income states with high Index scores (notably Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina and Oklahoma) also require their workers to pay disproportionately higher employee health insurance premiums. This is a double-whammy.

- Higher-cost health insurance (as measured by the Affordability Index) burden these low-income workers.

- These workers also must cover a higher percentage of their total health insurance costs from wages.

It’s no wonder that high costs now represent Americans’ greatest healthcare concern. It used to be access to high-quality healthcare services.

The West Virginia Anomaly

The most intriguing state is West Virginia. At $45,392, West Virginia has the nation’s third-lowest median household income. Only Mississippi and Louisiana are lower. At $20,252, West Virginia has the nation’s 7th highest cost for family health insurance.

The result is a staggering Affordability Index of 44.6, almost five points higher than the next highest score (Mississippi at 39.6). Here’s where it gets really interesting. Despite operating in a low-income state, West Virginia’s employers pay more for health insurance ($16,494) than employers in any other state. As a result, West Virginians contribute the 2nd lowest percentage (18.6%) of their total health insurance cost. At 15.1%, only Wisconsinites contribute a lower percentage.

It’s a good thing that West Virginia’s employers pay generously for health insurance benefits. The state has the highest percentage of people with preexisting medical conditions. (1) At the same time, West Virginia’s high healthcare costs relative to other low-income states inhibit its ability to attract new employers to the state.

Moreover, the opioid epidemic has walloped West Virginia. A December 2016 article in the Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that drug distributers delivered 780 million oxycodone and hydrocodone pills to West Virginia pharmacies between 2007 and 2012. That translates into 433 opioid pills for every man, woman and child in the state. During that period, 1,728 West Virginians died from overdosing on those drugs.

Outliers and Consequences

Not surprisingly, healthcare emerged as the top issue in West Virginia’s hotly contested 2018 Senate race between incumbent Democrat Joe Manchin and Republican Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. President Trump is very popular in West Virginia, carrying the state by 42% percentage points in the 2016 election, and he campaigned vigorously for Morrisey. West Virginians showed more concern for healthcare, however, voted overwhelmingly for Manchin and carried him to victory. (2)

The Healthcare Affordability Index illuminates the relationship between commercial health insurance costs and median household incomes. In the United States, high-cost health insurance funds a very high-cost healthcare delivery system. Despite the high healthcare expenditure, the U.S. ranks only 26th in life expectancy at birth among higher-income countries. (3) Healthcare spending doesn’t buy longevity.

As with Index scores, there is remarkable variation between individual states in life expectancy. At 81.3 years, Hawaiians live the longest lives while people in Mississippi live the shortest lives at 75.0 years – an enormous gap of 6.3 years. (4)

Moreover, there is general correlation among individual states between life expectancy and Index scores. People in states where the Index scores are lower live longer and vice versa. People in Hawaii and Minnesota live the longest and have among the lowest Index scores. People in Mississippi, Alabama and West Virginia experience the opposite.

Correlation is not causation. Poverty is the primary cause of life expectancy differences, and very poor people do not purchase commercial health insurance policies. Still, higher state-specific “burden” in funding commercial health insurance corresponds with shorter lifespans. Here is the dismal reality. America makes it harder for workers in low-income states to fund health insurance, and this dichotomy results in lower health status.

In good and bad ways, the United States is “exceptional.” The U.S. stands alone in overpaying for healthcare while tolerating subpar health outcomes and health status. This unfortunate reality exacts an enormous toll on the nation and its people. The American people carry unbearable healthcare burden that grows heavier each year.

Sources

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2018/10/23/race-for-the-senate-2018-key-issues-in-west-virginia/

- https://www.apnews.com/5ec995814f8b48cd90c7dcce89c5120a

- https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2016-annual-report/comparison-with-other-nations

- https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/life-expectancy/