October 20, 2022

Medicare Drug Price Negotiation: Real Savings or Just Another Shell Game?

The recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act includes provisions that allow Medicare to directly negotiate prices for both Parts B (physician-administered) and D (self-administered) prescription drugs. Given Medicare’s tremendous footprint in the drug market, the savings should be huge, right?

Not everyone agrees.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government will save $99 billion over ten years by allowing Medicare to negotiate for some prescription drugs beginning in 2026. Sounds like a lot, except the CBO baseline suggests total Part D spending of $2.2 trillion over the same time period, [1] meaning the savings will be about 4.5 percent of the total program. Not trivial, but not truly consequential either. Others estimate even smaller savings as manufacturers alter their product and pricing strategies to dampen the effects of the law. Let’s take a look.

Some History, First

The Part D program is fifteen years old. Prior to that time, prescription drugs for Medicare beneficiaries were paid for out of pocket or through supplemental insurance programs. There was no Medicare coverage for self-administered drugs.

The enactment of Part D heralded a new way of paying for and pricing goods and services to Medicare beneficiaries. Rather than the government setting prices, as it does for Parts A and B, a market-based approach determines the prices consumers pay. Part D is a premium support scheme in which the government subsidizes premiums, but beneficiaries are free to choose drug plans that best cover their drugs and suit their budgets for premiums and co-payments. The government sets the rules for Part D, but does not run the program

Even though the costs of the Part D program continue to be substantially below the original estimates of the program, the congressional democrats believe that the drug program costs, and costs to beneficiaries, are too high. They hold that prices can be lower if the government negotiates directly with drug manufacturers, rather than leaving that to insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers.

In many ways, politics around Part D reflect the philosophies of two opposing camps: those who believe that the market best allocates resources, and those who believe government decides best.

How “Negotiations” Will Work

In the simplest form, direct negotiations will begin in 2023 when the Secretary of HHS chooses ten drugs for negotiation from a list of the fifty highest expenditure “eligible” [2, 3, 4] drugs. The statute is vague as to how the Secretary will choose. It states the Secretary shall:

“Select from such ranked drugs with respect to such year the negotiation-eligible drugs with the highest such rankings.”

It is not at all clear what “highest such rankings” means. If the Congress wanted the Secretary to start at number 1 and end at number 10, Congress would have said so.

In fact, the statute (Sec. 1194 (b) (1)) gives the Secretary wide latitude to “develop and use a consistent methodology and process” for the selection of drugs and negotiation. Stand by for a 10,000-page regulation.

Assuming Secretarial discretion, let’s perform a thought experiment and put ourselves in the Secretary’s shoes for choosing drugs for negotiation. Further, let’s simplify the choices for the Secretary and constrain him or her to choosing five of the ten Part D drugs with the highest expenditures.

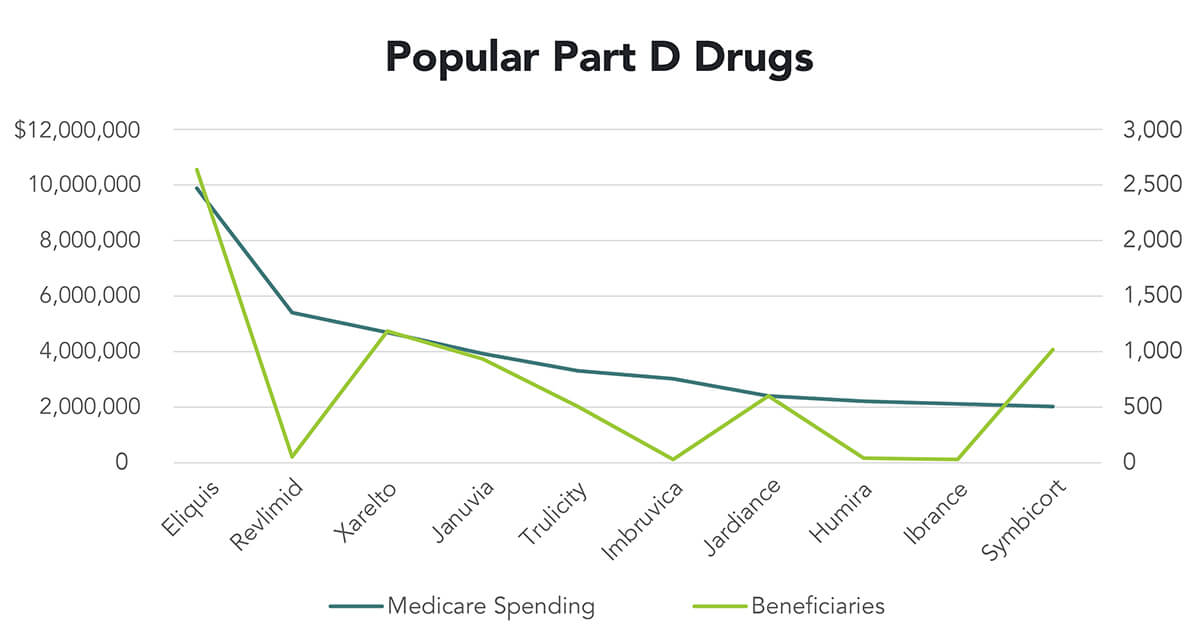

The chart shows the top Part D drugs by expenditure for 2020 and the number of Medicare beneficiaries using the drug. [5] Both axes are in thousands. For instance, Medicare spent $9.9 billion for Eliquis and covered 2.6 million beneficiaries. On the other hand, Revlimid cost Part D $5.4 billion but covered only 44,000 beneficiaries. [6]

So how does the Secretary choose?

- Total Expenditures — Assuming all are equally susceptible to negotiation, the Secretary would choose Eliquis, Revlimid, Xarelto, Januvia and Trulicity. This choice would make for an easy day at the office for the Secretary, and it conforms best with the statute.

- Total Beneficiaries — The Secretary could decide that the savings should accrue to the largest numbers of beneficiaries. That would mean Revlimid and Trulicity would be dropped from the list in favor of Symbicort and Jardiance. Meaning the beneficiaries with asthma get the savings not those with cancer. (Trulicity and Jardiance are both used to treat diabetes.)

- Value to Medicare — One of the founding concepts of Part D was that access to prescription drugs would lower overall Medicare costs. By properly managing illnesses with affordable medication, the government would avoid some hospital and physician costs. So with this Act, the Secretary could construct a framework (another 10,000-page regulation) that would measure value to Medicare. This rationale would choose drugs with high prices and low contributions to Medicare cost avoidance for negotiation.

- Overall Value — Most industrialized countries measure overall value of drugs using Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) or some other proxies of value. QALYs are a measure of duration of life, adjusted for the quality of that life. Despite considerable tinkering and considerable research, QALYs remain an imperfect measure of value. However, many countries accept them as a measure, for lack of anything better. The Secretary could choose from the list using QALYs as a basis. Drugs that have low QALY scores and high prices would be subject to negotiation. This would likely include expensive drugs that extend life for only a short time.

Rather than government dictated pricing, “3” and “4” above represent an opportunity to begin to reorient the Medicare program to value. The Secretary could choose to negotiate those drugs that have the highest prices but provide the lowest measurable value. Absent a market mechanism to do the same thing, this could be the start of a remarkable transformation in healthcare pricing.

The statute requires the Secretary to add new drugs in each subsequent year and provides more discretion in “choosing” which to add in 2028 and beyond. So even if the Secretary sticks with the Total Expenditure rationale above for the first couple of years, the other approaches are definitely available in the later years — and to future administrations.

The law outlines a process of negotiation that culminates in an agreement two years after the drug is initially chosen by the Secretary. If a company fails to negotiate or walks away from negotiations, they are subject to an escalating excise tax of 65 to 95 percent on the selected product. This is the same as saying “I’d like to negotiate for the price of your car, and, if you don’t, I will burn down your house.”

The law also contains other savings measures such as limiting the cost growth of prescription drugs used by Medicare beneficiaries to the rate of inflation. Those savings should not be confused with savings from “negotiation.”

A Craven Congress

As mentioned, the Congress has not been directive about which drugs will be negotiated along what schedule. Instead, Congress left that to the administrative apparatus. Why? Simple: deniability, campaign contributions and lobbying.

If the Congress was directive, individual Congresspeople would have to be responsible for their own vote and couldn’t shift responsibility to the administration. There would be no room for them to say “I didn’t vote for that” when negotiations cut the profits of their favorite pharmaceutical company. As it stands, Congresspeople can blame HHS/CMS and deride the “uncaring, faceless bureaucracy.”

Giving the Secretary discretion opens up the lobbying and contribution window. The slow-motion rollout of the statute means that there are many opportunities to change the law or influence and pressure the choices and process. Moreover, as hinted in “Total Beneficiaries” rational above, the Secretary’s discretion pits pharmaceutical companies against the so-called “disease groups.” Clashing battalions of lobbyists do not add to government savings. They do fill the campaign coffers of our elected representatives.

Three’s a Crowd

The popular press often portrays healthcare policy as a battle between two competing philosophies, those who believe that an open and free market best allocates resources, and those who believe government makes better decisions than the market.

The popular press often portrays healthcare policy as a battle between two competing philosophies, those who believe that an open and free market best allocates resources, and those who believe government makes better decisions than the market.

Neither side begins with clear concept of “value.” Other countries at least begin with a definition of value (see the discussion of QALYs) before debating whether the market or the instrumentality of government is best for pricing and coverage. The U.S. does not, though there is hope that the movement to value-based care can coalesce both camps around a common departure point.

The reality is that there are three parties at the negotiating table: two competing philosophies and an agnostic collective of lobbyists and fundraisers protecting small interests and small majorities. Well-dressed lobbyists beat naked philosophy every time. Expect them to prevail in this instance, as well.

As the government moves even deeper into regulating and controlling healthcare without a clear framework for value, we should be reminded of the words of the now sainted P.J. O’Rourke: “If you think healthcare is expensive now, wait until it’s free.”

Sources

- Linear extrapolation of the CBO baseline https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-07/51302-2021-07-medicare.pdf

- Author’s note: The statute exempts Orphan drugs, “low spend” drugs, human blood or plasma biologics, and small biotech drugs.

- Author’s note: Drugs eligible for negotiation must be sole source without generics. Small molecule drugs must have FDA approval for at least nine years, biologics at least thirteen years.

- Author’s note: The lobbyists were not asleep for this one.

- https://www.aarp.org/politics-society/advocacy/info-2022/medicare-prescription-drug-costs.html

- Author’s note: For the purposes of this thought experiment, we will assume all top ten drugs are eligible for negotiation. The statute includes Part B drugs as well. While their pricing schemes are different, the same analysis can apply.

Read Other Articles From Kerry Weems

- September 2022: Dobbs, Hyde and Sweaty Tourists

- June 2022: Dead Seniors Save Congress from Tough Decisions

- May 2022: Capitalism, Perversions, and Health Utilities

- February 2022: Death Math

- March 2021: Squared Up & Taking Shots: Our Stories from Vaccination Lines

- February 2021: What to Expect When You’re Expecting (A Budget)

- December 2020: Failing at Drug Price Reform

- November 2020: A Stalled Transition: Won’t Derail Biden’s Healthcare Team

- September 2020: A Pandemic Induced Collapse of the Way We Pay for Healthcare

- July 2020: Pandemic Preparedness: Beyond Bioterrorism & Federalism

- May 2020: Understanding Despair, Capture and Profiteering in American Healthcare

- February 2020: Advancing Advance Care Plans through Medicare: It’s Time to Move